In 1979, Sony co-founder Masaru Ibuka wanted to listen to opera music during long flights without disturbing other passengers. His engineers created a portable cassette player with lightweight headphones that weighed just 14 ounces. Nobody thought it would sell, cassette players were bulky home devices, why would anyone want music on the go?

The Sony Walkman became one of history’s most successful consumer electronics products. It sold 400+ million units across cassette, CD, and MiniDisc formats over 30 years. It created the portable music category that defined youth culture from the 1980s through early 2000s. It made Sony synonymous with personal audio the way Xerox meant photocopying.

Then Apple launched the iPod in 2001. Within five years, the iPod controlled 75%+ of portable music players while Walkman became a nostalgia brand struggling for relevance. Sony’s dominance evaporated so completely that most people under 30 don’t remember when Walkman meant portable music the way Google means search today.

This is the story of how Sony Walkman dominance created an entire product category, defined cultural movements, and generated billions in profits before missing the digital revolution that made their analog advantages worthless overnight. It’s a case study in how technology leaders fall when they optimize existing products instead of cannibalizing themselves.

How Sony Walkman Created the Portable Music Category

Before Walkman, portable music meant transistor radios or boom boxes carried on shoulders. The idea of personal music that only you could hear, played on a device fitting in your pocket, didn’t exist as a mainstream concept. Sony invented this category through product design brilliance rather than new technology.

The Walkman TPS-L2 launched in July 1979 combined existing components, cassette player mechanisms, miniaturized electronics, and lightweight headphones, in novel configuration. The insight was that removing recording and speaker functions could create a playback-only device small enough to carry anywhere.

Initial market research was negative. Sony surveyed potential customers who said they’d never buy a cassette player without recording capability. Akio Morita, Sony’s chairman, ignored the research and ordered 30,000 units manufactured. He believed the product would create its own demand once people experienced portable music.

Launch Strategy That Defied Convention

Early marketing challenges and solutions:

- No existing category: couldn’t position against competitors since none existed

- Skeptical retailers: stores hesitated stocking unproven product type

- Price concerns: $200 cost seemed high for playback-only device

- Youth targeting: focused on teenagers and young adults despite older demographic buying power

- Cultural positioning: marketed as lifestyle product rather than electronics

Sony deployed guerrilla marketing in Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park, hiring young people to walk around with Walkmans, letting curious passersby try the device. The experiential approach worked where traditional advertising couldn’t, people had to experience portable music to understand its appeal.

The strategy succeeded spectacularly. Initial 30,000 units sold out in three months. By 1980, Sony couldn’t manufacture fast enough to meet demand. The Walkman became cultural phenomenon in Japan before spreading globally through 1981-1982.

Global Expansion and Cultural Impact Through the 1980s

Sony Walkman dominance accelerated through the 1980s as the product transcended electronics to become cultural icon. By 1983, Walkman had sold 10+ million units globally. By 1989, that number reached 50+ million across multiple models and price points.

The product defined how people consumed music. Commuters listened during subway rides. Joggers ran with Walkmans clipped to waistbands. Students studied with background music. The yellow foam headphones and cassette tape belts became visual shorthand for youth culture in movies, TV shows, and advertising.

Culturally, Walkman enabled personal music experiences that reshaped social behaviors. People could create private audio spaces in public settings. Music became portable companion rather than stationary home entertainment. This individualization of music consumption presaged streaming era’s personalized playlists by 30 years.

Cultural milestones of Sony Walkman dominance:

- 1980: “Walkman” entered Oxford English Dictionary as generic term for portable music players

- 1981: First Walkman knock-offs appeared as competitors recognized category potential

- 1983: Sony sold Walkmans in 70+ countries with localized marketing

- 1984: Cassette sales surpassed vinyl for first time, driven partly by Walkman adoption

- 1986: “My Walkman” became common phrase in pop culture references

The business model was brilliantly simple. Sony profited from hardware sales with 30-40% gross margins on mid-range models. But they didn’t need recurring revenues because customers bought cassette tapes from music labels, creating self-sustaining ecosystem where Sony controlled player distribution while labels provided content.

Product Line Expansion Strategy

Sony didn’t rest on single model success. They released 300+ Walkman variants from 1979-2000 targeting different segments, budgets, and use cases. The Sports Walkman was water-resistant for athletes. The Pressman targeted journalists with recording capability. Premium models featured metal chassis and premium audio components for audiophiles.

This product proliferation maintained Sony Walkman dominance by blocking competitors from finding unserved niches. Every price point, every use case, every aesthetic preference had a Sony model designed for it. Competitors like Panasonic, Toshiba, and Aiwa competed on price but couldn’t match Sony’s brand prestige and product range.

The CD Walkman Era and MiniDisc Gamble

As compact discs replaced cassettes through the 1990s, Sony adapted with the Discman (initially called CD Walkman). Launched in 1984 at $300+, early Discmans were expensive and suffered from skipping issues when moved. But by 1990s, anti-skip technology and falling prices made CD Walkmans viable successors to cassette versions.

CD Walkman sales peaked in late 1990s, selling 10-15 million units annually. The product maintained Sony’s portable music dominance even as underlying technology shifted from analog tape to digital discs. But this success masked strategic vulnerability that would prove fatal.

In 1992, Sony launched MiniDisc format as next-generation Walkman technology. MiniDiscs offered digital recording, re-writable media, and compact form factor. Sony invested billions in manufacturing, marketing, and retail partnerships expecting MiniDisc to dominate portable music like cassette Walkman had.

Why MiniDisc Failed Despite Technical Superiority

MiniDisc technical advantages:

- Digital audio quality: superior to cassette analog sound

- Re-writable media: users could record, erase, and re-record unlike cassettes

- Compact size: smaller than cassettes with same playback time

- Track editing: digital format enabled easy track reordering

- Durability: encased media less prone to damage than cassette tape

Despite these advantages, MiniDisc failed to gain mainstream adoption outside Japan. The format faced chicken-and-egg problems where pre-recorded MiniDisc albums were scarce because player adoption was low, and player adoption stayed low because album selection was limited.

More fundamentally, MiniDisc arrived just as MP3 compression and internet file sharing began undermining physical media entirely. Sony’s billions invested in MiniDisc manufacturing represented catastrophic misreading of digital disruption already transforming music distribution.

Missing the Digital MP3 Revolution

While Sony perfected physical media players, teenagers in 1999 were downloading MP3 files from Napster and burning custom CDs. The MP3 format, standardized in 1993, compressed audio files to 1/10th size of CD quality, making internet music distribution practical for the first time.

Early MP3 players from Diamond Multimedia, Creative Labs, and others emerged 1998-2000. These devices stored 32-64 MB (roughly 30-60 minutes of music), far less than CD Walkmans but with game-changing advantage: no physical media. Users loaded music from computers via USB, eliminating need for cassettes, CDs, or MiniDiscs.

Sony, with its music label division (Sony Music Entertainment) and hardware manufacturing, faced internal conflicts that paralyzed digital strategy. The music label feared MP3 would enable piracy and cannibalize CD sales. The hardware division couldn’t release unrestricted MP3 players without angering the label division.

Strategic paralysis from corporate divisions:

- Sony Music: demanded copy protection making MP3 playback impossible or crippled

- Sony Electronics: wanted competitive MP3 players but couldn’t contradict music division

- Sony Computer Entertainment: PlayStation division focused on gaming, ignored music convergence

- Corporate leadership: failed to resolve division conflicts or force unified digital strategy

This internal conflict meant Sony’s first MP3 Walkman (NW-MS7) in 2000 didn’t support standard MP3 files. Users had to convert MP3s to Sony’s proprietary ATRAC format using clunky software. The user experience was so frustrating that Sony’s entry into digital music failed to gain traction despite Walkman brand strength.

How Apple Exploited Sony’s Strategic Paralysis

Apple watched Sony’s struggles and saw opportunity. Steve Jobs, returning to Apple in 1997, recognized that digital music was fragmenting across incompatible devices, formats, and software. The experience was terrible, but the market was growing rapidly.

Apple’s advantage was having no legacy music business or physical media investments. They could design for user experience without worrying about cannibalizing CD sales or protecting music label interests. This freedom let Apple build what customers actually wanted rather than what corporate politics allowed.

When iPod Killed Sony Walkman Dominance Forever

On October 23, 2001, Apple unveiled the iPod. The device held 1,000 songs (5 GB storage), synced with Mac computers via FireWire, and integrated seamlessly with iTunes software for music management. The tagline “1,000 songs in your pocket” immediately communicated value proposition that Sony’s fragmented strategy couldn’t match.

The iPod’s initial advantage wasn’t superior hardware, early reviews noted clunky scroll wheel and Mac-only compatibility. The advantage was integration. iTunes ripped CDs automatically, organized libraries intuitively, and synced with iPod effortlessly. Users didn’t think about formats, conversion, or compatibility, it just worked.

Sony’s response was slow and confused. They released multiple digital Walkman models 2002-2004 with different formats (ATRAC, ATRAC3, ATRAC3plus), incompatible software, and confusing model names. A customer walking into a store couldn’t easily determine which Sony model matched their needs or how it compared to iPod.

How iPod integration destroyed Sony’s advantages:

- Single iTunes software: users managed music in one place vs. Sony’s multiple programs

- Automatic format conversion: iTunes handled CD ripping and format conversion invisibly

- Content ecosystem: iTunes Music Store (launched 2003) offered 200,000+ songs legally

- Cross-device sync: buying song on computer automatically appeared on iPod

- Simple product line: iPod, iPod Mini, iPod Shuffle, clear differentiation vs. Sony’s 20+ confusing models

By 2004, iPod commanded 50%+ market share in portable music players. By 2006, that grew to 75%+. Sony Walkman became afterthought, selling a few million units annually versus iPod’s 50+ million. The 20-year dominance evaporated in five years as digital integration trumped hardware excellence.

iTunes Store as Strategic Moat

The iTunes Store, launching in 2003 with major label support, gave Apple content ecosystem that Sony couldn’t match despite owning a major music label. Sony Music’s contractual obligations to other device makers prevented exclusive iTunes-like store for Sony players.

Apple negotiated deals where purchased iTunes songs worked only on iPods (through FairPlay DRM), creating lock-in that made switching to competing players painful. Buy 500 songs from iTunes and you were invested in iPod ecosystem even if competitors released superior hardware.

This platform strategy, integrating hardware, software, and content, wasn’t new, Sony had executed it brilliantly with PlayStation consoles. But Sony couldn’t replicate platform thinking in music because internal divisions couldn’t agree on strategy that benefited the combined company versus individual divisions.

Sony’s Failed Attempts at Digital Comeback

Sony didn’t surrender easily. They launched multiple initiatives 2004-2010 trying to reclaim portable music leadership. None succeeded in reversing iPod’s momentum or restoring Sony Walkman dominance.

The Connect music store (2004) was Sony’s iTunes competitor offering DRM-protected downloads playable only on Sony devices. The service launched with 500,000 songs but suffered from complex software, confusing pricing, and format restrictions. Sony shut down Connect in 2008 after four years of losses.

Sony Network Walkman devices (2005-2007) finally supported MP3 files alongside ATRAC formats, belatedly matching compatibility that iPod had offered from launch. But by then, iPod’s ecosystem lock-in and cultural cachet made Sony devices seem like also-rans regardless of technical specs.

Strategic mistakes prolonging Sony’s decline:

- Format fragmentation: supporting ATRAC alongside MP3 confused rather than differentiated

- Software quality: Sony’s music management software remained inferior to iTunes through 2000s

- Brand dilution: launching phones, cameras, and other devices under Walkman brand weakened core identity

- Price positioning: premium pricing without clear superiority couldn’t compete with iPod value proposition

- Retail presence: Apple Stores showcased iPod experience while Sony relied on third-party electronics retailers

The final attempt was Android-based Walkman phones (2011-2013) positioned as music-focused smartphones. These devices competed against iPhone rather than iPod but faced same integration disadvantages that killed standalone Walkmans, Apple’s ecosystem (App Store, iCloud, iTunes) made switching costly despite Sony’s hardware quality.

What Sony Could Have Done Differently

With hindsight, Sony’s path forward seems obvious: cannibalize physical media early by launching unrestricted MP3 players in 1999-2000, build iTunes-equivalent software focusing on user experience over copy protection, and launch music store leveraging Sony Music catalog exclusively for Sony devices.

This strategy required killing profitable CD Walkman business before competition forced obsolescence. It meant ignoring Sony Music’s piracy concerns to prioritize customer experience. And it demanded unified corporate strategy over divisional autonomy.

Companies rarely make these choices. Innovator’s Dilemma predicts that successful companies optimize existing profitable businesses rather than cannibalizing them for uncertain digital futures. Sony followed this pattern perfectly, optimizing MiniDisc and CD Walkmans while iPod redefined portable music around digital integration.

Lessons from Sony Walkman’s Rise and Fall

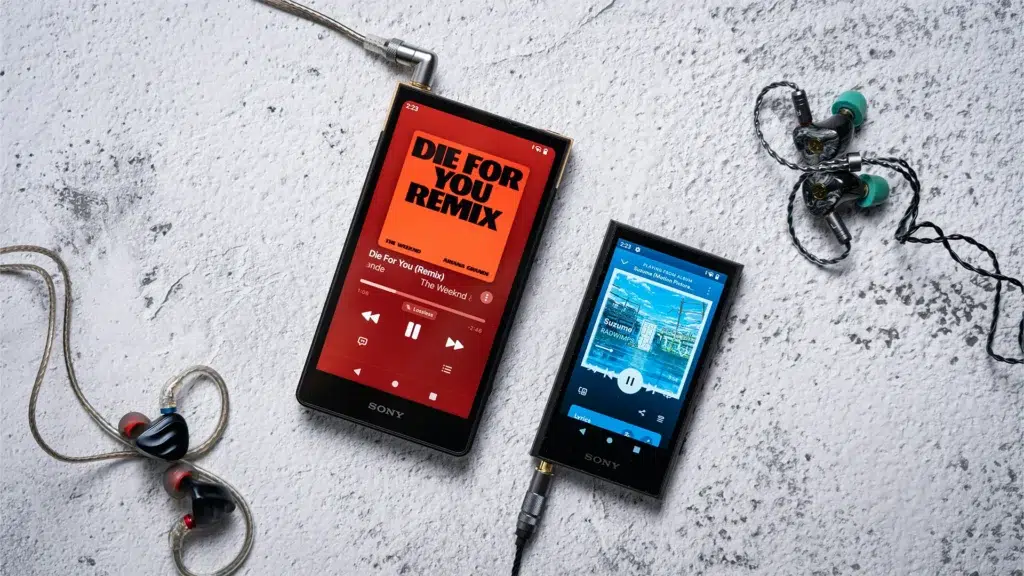

Sony Walkman dominance lasting 20+ years proves that category creation and brand building generate durable competitive advantages. Sony extracted billions in profits from Walkman across multiple technology generations. The brand remains valuable today, Sony still uses Walkman branding for digital audio products.

But the collapse demonstrates that past success doesn’t guarantee future relevance when technology platforms shift. Sony’s analog-era advantages, manufacturing excellence, retail distribution, brand prestige, became liabilities when digital integration and ecosystems mattered more than hardware quality.

The story also reveals organizational dysfunction’s role in strategic failure. Sony had resources, technology, and market position to compete with iPod. They owned music catalogs, manufacturing facilities, software engineers, retail relationships, everything needed to build iTunes-equivalent ecosystem. Corporate politics prevented unified strategy that could have preserved Sony Walkman dominance into digital era.

Why market leaders fail during technology transitions:

- Profit optimization: focus on maximizing existing profitable products vs. investing in disruptive alternatives

- Organizational silos: divisions protect their interests rather than company-wide strategy

- Customer satisfaction paradox: current customers love existing products, ignoring new customer needs

- Distribution channel conflicts: new models threaten existing retail relationships and margins

- Technology myopia: believing superior engineering will prevail over integrated experiences

Apple succeeded with iPod not through superior hardware but through integrated thinking that Sony’s organizational structure prevented. The iPod itself was unremarkable, 1.8-inch Toshiba hard drive, standard components, thick design by 2001 standards. The integration of hardware, iTunes software, music store, and eventually iPhone made the ecosystem irreplaceable.

The Bottom Line

Sony Walkman dominance from 1979-2000 represents one of consumer electronics’ greatest success stories. The product created portable music category, generated 400+ million unit sales, and established Sony as premium audio brand. Walkman wasn’t just product, it was cultural phenomenon defining how generations experienced music.

The collapse from 2001-2006 is equally instructive cautionary tale. Apple’s iPod destroyed Sony’s leadership not through superior hardware but through integrated ecosystem thinking that made entire product category obsolete. Physical media players, Sony’s strength, became irrelevant when digital libraries and online stores redefined portable music.

What made Sony Walkman dominant initially:

- Category creation: invented portable personal music before competitors recognized opportunity

- Product design: lightweight, portable form factor with quality audio

- Brand building: consistent marketing making Walkman synonymous with portable music

- Format agility: successfully transitioned from cassette to CD maintaining dominance

- Distribution scale: global retail presence in 70+ countries

What enabled iPod to destroy Walkman:

- Digital integration: iTunes + iPod + Music Store ecosystem vs. fragmented Sony devices

- User experience: prioritized simplicity over features or format purity

- Organizational focus: Apple had no legacy music business creating internal conflicts

- Platform lock-in: purchased content worked only on iPods creating switching costs

- Retail control: Apple Stores showcased experience vs. third-party electronics retailers

For businesses studying this case, the lessons are clear but painful. Past market dominance doesn’t protect against platform shifts that make core competencies irrelevant. Organizational structure and incentives matter as much as technology capabilities when responding to disruption. And sometimes the best strategic move is cannibalizing your own successful products before competitors force obsolescence.

Sony’s experience also demonstrates that recovery from strategic failure is possible but difficult. The company remains profitable today through diversified businesses including PlayStation, image sensors, and entertainment content. But they never regained portable music leadership lost to Apple, and later to smartphone streaming.

The ultimate irony: Sony invented portable personal music with Walkman but Apple captured the category’s digital evolution with iPod and iPhone. The same cultural shift Sony created in 1979, making music personal and mobile, Apple exploited in 2001 through better integration and ecosystem thinking. Sony taught the world to want portable music, then forgot those lessons when technology changed.